When Policies Collide – Untangling “Other Insurance” Clauses

At our recent London Symposium, Associate Abigail Smith discussed the potential challenges posed by other insurance clauses in insurance policies. The session covered:

- The genesis of these clauses;

- The types of other insurance clauses used to limit an insurer’s liability in the event of double insurance; and

- How competing other insurance clauses are interpreted, in practice.

What is double insurance?

Double insurance occurs when the same party is insured with two or more insurers in respect of the same interest on the same subject matter against the same risk. In other words, it occurs where an insured’s loss is covered under two or more separate policies. Whilst it can be a commercially prudent guard against insurer insolvency, it most often arises inadvertently (for example, where a composite policy overlaps with dedicated cover).

The common law position

Under common law, a policyholder that is double insured for its loss can claim against whichever policy or policies it chooses, in whichever order it chooses, subject to each policy’s limits. Then, to ensure the risk is fairly distributed between insurers, the paying insurer is entitled to claim a contribution from the non-paying insurer (a principle known as rateable contribution – Drake v Provident [2003]).

Industry challenges

Unfortunately, the common law position gives rise to some complicated issues.

The main issue is that, because there is no general rule or common law duty requiring a policyholder to disclose that it is double insured, unless an insurer asks the question directly, or notification of other insurance is a condition of the policy, a paying insurer may not be aware that they are entitled to claim a contribution.

Adding another layer of complexity, the limitation period for bringing a contribution claim is two years from the date that the right accrued under section 10(1) Limitation Act 1980. That date, which is likely to be the date of a judgment, settlement or arbitration award, is not necessarily when an insurer becomes aware that they are entitled to a contribution. In fact, with no duty to disclose, it is possible for limitation to expire without an insurer ever knowing that it had been entitled to a contribution.

Types of “other insurance” clauses

It was in recognising these challenges that the industry came up with a solution: other insurance clauses, which are standard clauses in insurance policies which limit an insurer’s liability in circumstances where another policy covers the same loss.

In The National Farmers Union Mutual Insurance Society Limited v HSBC Insurance (UK) Limited [2011], Gavin Kealey KC identified 3 main types of other insurance clauses, being:

- Escape Clauses – those that exclude cover altogether in the event that another policy covers the same loss.

- Excess Clauses – those that state that the policy will only respond in excess of any other insurance.

- Rateable Proportion Clauses – those that limit an insurer’s liability in proportion to the total cover available.

Abigail explored how each type of clause is interpreted, and how competing clauses interact, in practice.

Escape Clauses

Owing to the fact that Escape Clauses seek to exclude cover altogether in the event of double insurance, there was at the outset the potential for policyholders to be left without any cover at all where two or more policies each included an Escape Clause.

That issue was addressed in Weddell v Road Transport [1932], with the Court ruling that it would be unreasonable to leave a policyholder without any primary cover in circumstances where multiple policies were in place and multiple premiums had been paid. As such, where two or more policies include an Escape Clause, they will cancel each other out so that the policyholder can claim against whichever policy (or policies) it chooses (essentially reverting to the common law position).

Excess Clauses

The same question was more recently considered in Watford Community Housing v Athur J Gallagher Insurance Brokers Limited [2025], this time in respect of Excess Clauses. Ultimately, the Commercial Court held that, because Excess Clauses also seek to avoid primary liability in the event of other insurance, they cancel each other out in the same way that Escape Clauses do.

Escape Clause v Excess Clause

Whilst there’s no English authority addressing a scenario in which two or more policies include competing Escape and Excess Clauses, Australian caselaw does provide some assistance.

In Allianz Insurance Australia Ltd v Certain Underwriters at Lloyds of London [2019] the New South Wales Court of Appeal held that competing Escape and Excess Clauses would also cancel each other out on the basis that both seek to avoid primary liability in the event of double insurance – an Escape Clause seeks to avoid any liability, whilst an Excess Clause recognises only a secondary one.

The New Zealand courts, by contrast Abigail noted, have on one occasion reached the conclusion that an Escape Clause will prevail (albeit relying heavily on the insurance provisions in an underlying contract). As such, the outcome will always come down to the specific policy wording and the wider context; “there is no universal hierarchy that automatically applies.”

Rateable Proportion Clauses

The final type of other insurance clause limits an insurer’s share of the loss in proportion to the policy limit. For example:

- An insured incurred £900,000 of loss covered under two separate policies.

- Policy A with a limit of £1m, and Policy B with a limit of £2m.

- Policy A’s insurer would be liable for 1/3 of the loss (their £1m portion of the total £3m insured), which is £300,000, and Policy B’s insurer would be liable for 2/3 which is £600,000.

If Policy A contained a Rateable Proportion Clause, and Policy B was silent, Policy B’s insurer would have to pay the whole of the loss and then claim a contribution from Policy A’s insurer.

Rateable Proportion Clause v Escape / Excess Clause

Unlike Escape and Excess Clauses, Rateable Proportion Clauses acknowledge that an insurer does have a primary liability in the event of other insurance, albeit a limited one. For that reason, an Escape or Excess Clause will prevail over a Rateable Proportion Clause.

If Policy A included a Rateable Proportion Clause whilst Policy B included an Escape Clause, the effect of the Escape Clause is that there would be no double insurance and Policy A’s insurer would be liable for the loss without being entitled to claim a contribution from Policy B’s insurer.

Whilst there has been some controversy over how an Excess Clauses might compete with a Rateable Proportion Clause (Austin v Zurich [1944]), in NFU v HSBC, Gavin Kealey KC sought to clarify the position. He remarked that, as a matter of construction, an Excess Clause should prevail over a Rateable Proportion Clause because a Rateable Proportion Clause recognises that an insurer has a primary liability in the event of double insurance, whereas an Excess Clause does not.

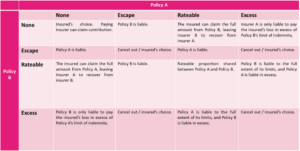

Abigail produced the table below as a starting guide for interpreting competing clauses, but was careful to note that the position will always depend on the policy wording, and the wider context.

Remaining questions

One issue that the courts are yet to address is whether, where an insured has multiple policies forming a horizontal primary layer of cover, followed by an excess layer that sits above, the entire horizontal layer must be exhausted before the excess policy responds.

The issue hasn’t arisen in caselaw to date, but Abigail remarked that it will be interesting to see how the courts approach the question when the times comes.

Key takeaways

The good news, for policyholders, is that the courts have so far refused to entertain any scenario in which an insured is left without primary cover.

That doesn’t mean, Abigail warns, that other insurance is an insurer’s problem. In circumstances where an Escape or Excess Clause prevails, an insured can be left without access to a policy that it paid a premium for, and which may well be preferable on its terms. Similarly, the disadvantage of Rateable Proportion Clauses from an insureds point of view is that the risk of insurer insolvency transfers back to the insured.

For those reasons, it is worth understanding whether there is another policy that responds to a risk and, if so, how any other insurance provisions might be interpreted.

Author

Abigail Smith, Associate

When Clauses Collide: Court of Appeal Backs MRC Over New York Arbitration

A recent Court of Appeal decision, Tyson International Company Ltd v GIC Re, India, Corporate Member Ltd [2026] EWCA Civ 40, provides valuable clarification on the approach taken by English courts when confronted with conflicting jurisdiction and arbitration provisions contained within layered reinsurance documentation.

Background:

Tyson International Company Ltd (“TICL”) is the Bermudan captive insurer for Tyson Foods, a major US‑based global food producer. In 2021, TICL arranged facultative reinsurance for its property risks with several reinsurers, including GIC Re, India, Corporate Member Ltd (“GIC”).

Two layers of facultative reinsurance were first placed on 30 June 2021 by way of a London Market Reform Contract (the “MRC”). The MRC provided for English governing law and contained a clause granting the courts of England and Wales exclusive jurisdiction over all matters relating to the reinsurance.

On 9 July 2021, this placement was supplemented by the execution of a second set of contracts in the form of the Market Uniform Reinsurance Agreement (the “Certificate”). The Certificate, instead, required disputes to be resolved by arbitration in New York under New York law. They also incorporated three amendments, the second of which stated that the MRC would “take precedence over reinsurance certificate in case of confusion” (the “Confusion Clause”).

A fire at a Tyson Foods facility in Hanceville, Alabama on 30 July 2021 gave rise to a claim under the captive policy. TICL accepted coverage and notified GIC. GIC later purported to rescind its reinsurance participation based on alleged misrepresentation relating to property valuations. TICL commenced proceedings in England relying on the jurisdiction clause in the MRC, while GIC sought to compel New York arbitration under the Certificate.

At first instance, the Commercial Court granted TICL a permanent anti‑suit injunction restraining GIC from pursuing the New York arbitration. In response, GIC appealed to the Court of Appeal.

Parties’ positions and key issues:

GIC’s principal argument was that the Confusion Clause was narrow in scope and applied only to internal drafting inconsistencies within the Certificate itself. GIC also maintained that, even if the clause applied more broadly, the English jurisdiction clause in the MRC and the New York arbitration clause in the Certificate should be read together in a manner that gave effect to both, with the English courts assuming a supervisory role over arbitration in New York.

TICL submitted that the Confusion Clause operated as a genuine hierarchy provision intended to resolve inconsistencies between the two documents. Once invoked, it required the English governing law and exclusive jurisdiction provisions in the MRC to prevail, leaving no room for the New York arbitration clause to operate.

Hence, the key issues for consideration were:

- The proper construction of the Confusion Clause; and

- Whether the English jurisdiction clause in the MRC and the New York arbitration clause in the Certificate could operate together

Analysis:

- The proper construction of the Confusion Clause:

GIC submitted that the Confusion Clause applied only where the Certificate itself contained internal inconsistencies and did not extend to conflicts between the Certificate and the MRC. The Court rejected this interpretation. It held that the natural and commercially coherent meaning of the wording was that it addressed inconsistency arising between the two documents. The MRC and Certificate were executed nine days apart and contained materially different provisions; it was, thus, far more plausible that the clause was intended to identify the document that should prevail where such differences arose.

Critically, the Court also commented that GIC’s narrow construction would be commercially unsound in rendering the clause ineffective when the most obvious form of “confusion” occurred; namely, a contradiction between the documents themselves.

- Whether the English jurisdiction clause and New York arbitration clause could operate together?

GIC argued that even if the MRC prevailed, the English jurisdiction clause could be read as supervisory or auxiliary to New York arbitration. The Court, however, rejected this in finding that the MRC conferred exclusive jurisdiction on the English courts in clear and unqualified terms, while the Certificates mandated binding arbitration in New York. To reinterpret the English clause as merely supervisory would invert the contractual hierarchy expressly agreed through the Confusion Clause and substantially distort the meaning of the exclusive jurisdiction provision.

The permanent anti‑suit injunction was, therefore, correctly granted.

Conclusion:

The decision provides clear confirmation that ordinary principles of contractual interpretation remain paramount in resolving disputes arising from inconsistent reinsurance documentation. The Court emphasised that where parties have chosen express language, particularly as to precedence, the courts will give effect to that language according to its natural and literal meaning. It is not the role of the court to retrospectively correct what may, in hindsight, be commercially disadvantageous to one party, nor to remodel the parties’ bargain by reading fundamentally inconsistent clauses together.

Authors

Michael Robin, Partner

Pawinder Manak, Trainee Solicitor

Motor Finance and the FCA Redress Scheme: Insurance Coverage implications for policyholders

Background and Supreme Court Decision

The UK Supreme Court’s judgment in Hopcraft v Close Brothers Ltd, together with Johnson & Wrench v FirstRand Bank Limited [2025] UKSC 33, clarified the law on secret commissions in motor finance. The Court held that car dealers arranging finance do not owe fiduciary duties to customers, which removed the foundation for claims based on breach of fiduciary duty. It also confirmed that English law does not recognise a free‑standing tort of “bribery” or secret commission absent a fiduciary relationship.

However, the Court significantly tightened the standard for commission disclosure. It held that a statement that “a commission may be paid” is inadequate: lenders and brokers must disclose both the fact and the amount, or the basis, of any commission prior to the finance agreement being signed. The Court reaffirmed that undisclosed or partially undisclosed commissions can render a lender–borrower relationship “unfair” under section 140A of the Consumer Credit Act 1974.

In Johnson, the Court found an unfair relationship where an entirely undisclosed commission – approximately 55% of the total loan– created a misleading impression and contributed to the unfairness. This was held to be sufficiently opaque and extreme to create an unfair relationship, leading to an order that the lender refund the commission together with interest. In the other joined cases, however, the commission arrangements were either less substantial or subject to some level of disclosure, and the borrowers did not obtain relief. The Court also held that lenders can only be liable as accessories to a dealer’s misconduct if they acted dishonestly, which was not established on the facts.

FCA Industry‑Wide Redress Scheme

In response to the judgment, the FCA announced an industry redress scheme under s.404 FSMA, covering motor finance agreements entered from April 2007 to November 2024. The FCA has estimated that approximately 14 million agreements involved undisclosed or excessive commissions, and that around 44% (about 6.2 million loans) may be considered unfair under the new standards.

The FCA published its consultation on the mechanics of the scheme in December 2025, with responses due in early 2026. The FCA has indicated that, subject to feedback, the final rules are expected to be issued in mid‑2026, with the redress scheme going live shortly thereafter

Compensation is expected to average £700 per loan, which implies a total payout of around £8.2 billion, with the possibility that it could reach £9–10 billion. Firms will additionally incur substantial operational expenditure, estimated at £2.8 billion, to administer the scheme. Any FCA fines for misconduct would be imposed separately and would not form part of the compensation pool.

The proposed scheme requires lenders to identify affected customers and provide compensation directly. Dealers and brokers will be expected to supply relevant information, and lenders may attempt to recover a portion of the cost from brokers via indemnity arrangements.

Application to FI Liability Policies:

Motor finance lenders and brokers will look primarily to their professional indemnity (PI) or civil liability policies, and, in certain circumstances, to D&O policies. Many of these policy wordings will be bespoke to Financial Institutions (FIs).

FI PI policies cover claims arising from wrongful acts in the insured’s provision of professional services, which is likely to include providing consumer credit and complying with regulatory disclosure obligations. Many FI PI policies define a “Claim” in broad terms, often including civil claims and regulatory proceedings that could result in an order requiring payment of compensation. An FCA-mandated redress scheme is likely to fall squarely within this definition.

Moreover, if a firm fails to make the payments required under s.404 redress scheme, the FCA can treat that failure as a breach of its rules under s.404F(7) and use the full range of its enforcement powers, including directions, financial penalties and public censure, to compel compliance, while consumers also have a direct right of action under s.404B(1) to sue for the compensation owed. Additionally, the FCA may apply to the courts under its general powers (including ss.380–382 FSMA) to obtain orders compelling a firm to remedy the breach, meaning that both the FCA and the courts ultimately can require an FI to pay compensation. Hence, any such proceedings would, likely, satisfy the definition of a “Claim” sufficient to engage the insuring clause for cover.

Notwithstanding, various coverage issues may still arise as follows.

Key Coverage Issues

Issue 1: Whether Commission Refunds Constitute an Insured “Loss”

A central coverage question is whether returning commission and interest constitutes an insured “Loss.” PI policies usually cover damages or compensation that the insured is legally liable to pay. A redress scheme under s.404 can only compensate customers where they have a private legal remedy so insureds who pay compensation should be able to demonstrate to insurers that they had a legal liability.

As regards loss, the proposed redress scheme generally seeks to restore consumers to the position they would have been in if commissions had been properly disclosed, which suggests a compensatory purpose. However, there is no causation requirement under the FCA’s proposals, in that consumers will not have to prove that they would not have entered into the loan if full disclosure had been made (although the presumption that non-disclosure caused loss is rebuttable by lenders in certain circumstances, e.g. if the consumer was deemed to be “sophisticated”).

Insurers may argue that part of the relief is restitutionary because it involves disgorging a commission that the insured (or its agent) earned. Many PI policies exclude loss consisting of the return of fees or commissions. Some policies include “carve‑backs” where commissions are linked to a wrongful act by an employee, which can restore cover. Courts and insurers often distinguish between returning an improper gain (normally uninsurable) and compensating a third party’s financial loss (insurable).

While there remains a grey area, especially under policies that expressly exclude “improper profit,” it is likely that courts will view these payments as compensatory and therefore insurable. Nonetheless, disputes may arise where policy language is particularly broad or where a settlement includes elements that resemble pure disgorgement.

Issue 2: Regulatory Fines and Penalties

Although consumer compensation would probably be covered, regulatory fines are not. FI PI policies universally exclude fines, penalties, and punitive damages, either expressly or on the basis that they are uninsurable by law. Any FCA fines imposed in parallel to the redress scheme will therefore fall outside insurance cover. Statutory interest added to customer compensation is generally considered part of the damages and is normally covered.

Issue 3: Claims‑Made Basis and Notification

FI PI policies operate on a claims-made basis, making notification a central coverage issue. Many claims will arise in 2025–2026 when consumers complain or are deemed to do so under the scheme. Policies in force at that time should respond unless exclusions for known circumstances apply.

Insurers may seek to frame a failure to disclose commission levels as a material non-disclosure. This would require an insurer to show (i) the information would have influenced a prudent insurer in setting terms, and (ii) the policyholder knew (or ought reasonably to have known) the information. Historically, however, commission setting practices in motor finance were industry‑standard, widely known, and the regulatory risk was already in the public domain due to the FCA’s 2019 work. All of that, will make it harder for insurers to say they were “unaware” of the risk, or that non‑disclosure was material in a fair‑presentation sense.

Insurers are closely examining such arguments but are aware that the hurdle is relatively high, particularly as many had opportunities during renewals to ask targeted questions and add exclusions specifically targeting motor finance commission issues, as occurred with Arch Cru and BSPS.[i]

The effectiveness of “circumstance notifications” is, therefore, critical. Notifying when the Court of Appeal judgment was issued or when the Supreme Court granted permission to appeal would have preserved cover in the corresponding policy period, but insurers may argue that any such notifications were too late and not in accordance with the policy provisions. There may be disputes over when circumstances crystallised to the point of being notifiable. English case law suggests that something more than a remote possibility of claims is required, and the Court of Appeal’s expansive judgment in relation to commission disclosure arguably met that threshold.

Issue 4: Aggregation

Given the potential number of claims, aggregation will have a major impact on available limits and deductibles. PI policies often state that a series of related or continuous acts or omissions will be treated as a single claim, or that claims arising from the same originating source are treated as a single claim.

Depending on the policy wording therefore, all instances of inadequate commission disclosure by a single lender may constitute one aggregated claim.

This approach would benefit insurers in that it would cap the insurer’s liability at a single policy limit (often £10–20 million), regardless of the scale of consumer redress.

However, it would also benefit insureds in that it would mean that only one deductible applies.

Issue 5: Allocation Issues

Where a regulatory proceeding includes both compensatory and non‑compensatory elements, policies usually require allocation between covered and uncovered parts. Although fines are excluded, defence costs for regulatory investigations are often almost fully covered because the work typically relates to the compensatory issues as well.

Further, if policies do not provide for allocation, in accordance with the principle expounded in Wayne Tank and Pump Co Ltd v Employers Liability Assurance Corp [1974] QB 57, where regulatory proceedings are proximately caused by both covered and excluded matters, insurers may argue that the exclusion will prevail to preclude cover. However, it is important to note that Wayne Tank is not in fact authority that defence costs caused by two concurrent and interdependent proximate causes will be excluded, and the actual position is likely to turn on careful analysis of the policy (and the facts, as regards the reasons defence costs were incurred).

Wider Implications for Insurers and Intermediaries

This episode has substantial implications for financial services and insurance markets. PI underwriters are likely to adopt more restrictive terms, including specific exclusions, reduced limits, and higher deductibles. There may also be increased scrutiny of other products involving commission structures, such as mortgage broking or insurance distribution.

The scale of the redress means insurers will need to increase reserves and manage potential disputes within insurance towers, especially regarding aggregation and allocation. Insurers may also look to pursue subrogated claims against brokers under indemnity agreements. Reinsurers will also be significantly affected.

The ruling and redress programme reinforces the importance of transparency in remuneration across all intermediary sectors. Insurance brokers and financial intermediaries should reassess commission disclosure practices in light of the FCA’s broader focus on consumer fairness and the new Consumer Duty. Firms that continue opaque practices may face both regulatory scrutiny and increased insurance restrictions.

Although D&O exposure will, hopefully, be limited, senior managers may also face FCA attention under the Senior Managers & Certification Regime.

Conclusion

The motor finance commission litigation and resulting FCA action create extensive compensatory liabilities for lenders. FI PI policies are likely to respond, subject to limits, aggregation, notification requirements, and exclusions for fines and proven dishonesty. Commission refunds are most likely to be treated as compensatory and therefore insurable. The case underscores the importance of transparent consumer practices, early notification under claims‑made policies, and careful review of policy wording in the context of large‑scale regulatory actions.

[i] Arch Cru was a mis‑selling scandal involving investment funds marketed as low‑risk but in fact exposed to high‑risk, illiquid assets. When the funds collapsed in 2009, the FCA established a consumer redress scheme, and although many PI insurers argued that firms had breached the duty of fair presentation by failing to flag emerging regulatory concerns, those arguments were largely unsuccessful because the issues had already been widely publicised. Insurers later introduced Arch Cru‑specific exclusions once the risks became well known.

BSPS involved unsuitable advice given to steelworkers to transfer out of the British Steel Pension Scheme into riskier personal pensions. The FCA subsequently implemented a statutory redress scheme, and PI insurers again sought to rely on fair‑presentation breaches, but these arguments similarly gained little traction because the regulatory concerns were already in the public domain by the time many policies renewed. Insurers ultimately responded by adopting BSPS‑specific exclusions as the scale of the issue became apparent.

Authors

Chris Ives, Partner (Head of Financial Institutions)

Jonathan Corman, Partner

Pawinder Manak, Trainee Solicitor

A Vivid Reminder: Fire Safety Defects Can Trigger Cover

Ten years on from Grenfell, fire safety defects remain one of the defining issues in the built environment. Against that backdrop, the recent decision in Vivid Housing Ltd v Allianz Global Corporate & Specialty SE [2025] offers important guidance on how the courts approach ‘imminent damage’ and reinforces the need for insurers to be part of the solution rather than an obstacle to remediation.

At Fenchurch Law, we have advised on several imminent danger cases, an example being Nova House, Slough – which involved a variety of fire safety and structural issues. The decision in Vivid, which involved an application for summary judgment, sits squarely within this developing line of authority and offers policyholders helpful clarity.

The Policy

The operative clause at the heart of this application is Clause 3(a), which states:

Clause 3(a) Operative Clause

"The Insurers agree to indemnify the Insured against the cost of repairing, replacing and/or strengthening the Premises following and consequent upon a Defect which becomes manifest and is notified to Insurers during the Period of Insurance and not excluded herein causing any of the following events:

(i) destruction of the Premises; or

(ii) physical damage to the Premises; or

(iii) the threat of imminent destruction or physical damage to the Premises which requires immediate remedial measures for the prevention of destruction or physical damage within the Period of Insurance."

The Dispute

Vivid submitted a claim in May 2019, contending that several building safety defects had manifested at the Property, and that they all fell within the Policy's definition of "Defect", thereby triggering the Operative Clause. Allianz denied that contention.

The summary judgment application focused solely on the meaning and scope of sub-clause(iii):

"the threat of imminent destruction or physical damage to the Premises which requires immediate remedial measures for the prevention of destruction or physical damage within the Period of Insurance."

The key question here, assuming that there were such “Defects”, was whether there was a risk of imminent damage.

The Defects

- Defect 1 (Rockpanel cladding): Vivid alleged that combustible RP cladding and foam insulation were used on a building over 18m high without proper testing or barriers. It also said that combustible debris in cavities could enable fire and smoke to spread externally.

- Defect 2 (vertical cavity barriers): Vivid contended that required vertical cavity barriers were missing, allowing fire or smoke to spread unnoticed throughout the building.

- Defect 3 (horizontal cavity barriers): Vivid claimed that missing or faulty cavity barriers at party walls, slab edges, and window openings could allow fire and smoke to spread undetected throughout the development.

- Defect 4 (Rockclad bracketry): Vivid states that RP cladding panels were not properly secured to vertical rails, with brackets that were inadequately supported or overstressed, posing a risk of detachment or damage.

- Defect 5 (building debris): Vivid claimed that debris left in building cavities created a fire hazard, facilitated fire spread, and enabled water to enter flats, causing further damage.

Allianz’s Position

Allianz argued that “imminent” required a serious and immediate likelihood of damage occurring soon, which it said was not the case as of August 2019.

In their view, the clause did not cover threats that would materialise only if a non-imminent event occurred, nor extend to circumstances where remedial measures are not immediately necessary to prevent destruction or damage within the policy period.

There was no likelihood of damage occurring soon as at August 2019, Allianz said, because:

(i) Vivid’s response in the notification to whether urgent repairs were required was “N/A.”

(ii) The only measures implemented during the policy period were “Waking Watch” arrangements, which were not intended to prevent property damage.

(iii) No damage occurred during the policy period, despite the absence of remedial works.

Vivid’s Position

Vivid, by contrast, contended that “imminent damage” should be assessed objectively, and that there was no requirement that the destruction or physical damage should happen soon. On its proper construction, they said that sub-clause (iii) applied where a reasonable observer would conclude that there was a realistic prospect of physical damage requiring immediate remedial measures to prevent it.

As to each of the defects, Vivid argued that:

(i) Defects 1, 2, 3 and 5 made the development vulnerable to physical damage in the event of fire, giving rise to a realistic prospect that imminent physical damage might occur. That risk was constant given the frequency of fires, supported by evidence of similar incidents.

(ii) Defect 4 put the cladding panels and bracketry at risk of deformation and detachment, giving rise to a realistic prospect that imminent physical damage might occur.

The Court’s Decision

The Court considered whether the defects created a threat of imminent destruction or damage sufficient to engage the policy.

As to the fire safety defects, the Court held that it could not be said there was no realistic prospect of establishing a serious risk of fire and imminent damage, particularly given the implementation of Waking Watch measures, which reflected an ongoing fire concern. Put differently, the presence of a Waking Watch did not undermine the concern of a present or imminent danger. Quite the opposite, it was that very concern which required the Waking Watch to begin with.

The court emphasised that the policy required not only an imminent threat but also that immediate remedial works are necessary to prevent destruction or damage within the period of cover. Whether this threshold is met is fact-sensitive; typically, imminent threats necessitate immediate repair or mitigation. Temporary measures such as Waking Watch do not negate the need for remedial works.

Ultimately, the court concluded:

"Vivid’s case on the construction of the policy clause and whether the policy responds has a real prospect of success in relation to all Defects other than Defect 4, and the application for summary judgment is refused."

In respect of Defect 4 (Rockclad bracketry), which was unrelated to fire risk, the Court found in Allianz’s favour and granted summary judgment.

For Defects 1, 2, 3 and 5, the Court accepted that the fire‑related risks created a realistic prospect of imminent damage.

ANALYSIS

Why Did the Court Exclude Defect 4?

Defect 4 involved the risk of deformation and detachment of cladding panels and bracketry. Intuitively, one might say this creates a clear risk of physical damage. However, the court held that the defect did not amount to a fire‑related risk and did not require “immediate remedial measures” to avoid destruction or damage within the policy period.

Two nuanced reasons are at play:

- Immediacy: the deformation risk was progressive, not acute.

- Requirement for immediate works: unlike fire safety defects, the defect did not necessitate urgent intervention to avoid catastrophic loss.

This highlights a key theme in imminent danger cases: the immediacy of required remedial work often drives the outcome more than the nature of the defect itself.

Why Vivid Matters

Similar wording has been scrutinised before, most notably in Manchikalapati & others v Zurich Insurance plc & others [2019] (“Zagora”), and the court’s approach in Vivid aligns with and develops that earlier guidance.

In Zagora, the court held that imminence requires a real and present risk, not a remote or hypothetical possibility. Vivid adopts that framework but clarifies how it applies to fire safety defects, emphasising:

- fire events are inherently unpredictable;

- where fire‑related defects exist, the risk of damage is constant; and

- temporary measures (e.g., Waking Watch) do not remove the underlying risk.

CONCLUSION

The decision in Vivid is consistent with previous case law and provides helpful confirmation that:

- Fire safety defects can constitute imminent danger;

- Temporary measures such as Waking Watch do not exclude immediacy;

- The courts will continue to apply the principles developed in Zagora; and

- Insurers must recognise their role in enabling, rather than hindering, fire safety remediation.

For policyholders, the judgment offers helpful reassurance. For insurers, it is a reminder that narrow constructions of imminent danger are increasingly difficult to sustain.

Importantly, policyholders should not be required to wait for an actual fire incident before their insurance coverage becomes applicable. The judgment clarifies that waiting for harm to occur before responding to the risk is both unreasonable and contrary to the purpose of fire safety provisions.

Chloe Franklin is an Associate at Fenchurch Law

New Guidance on the Scope of RCOs: The Upper Tribunal’s Judgment in Edgewater (Stevenage) Limited and Others v Grey GR Limited Partnership

Last week, the Upper Tribunal (Lands Chamber) (“UT”) handed down its judgment in a highly-anticipated appeal against a swathe of Remediation Contribution Orders (“RCOs”), providing further guidance on the scope of section 124 of the Building Safety Act 2022 (“BSA”).

In dismissing the appeal on all grounds, Mr Justice Edwin Johnson confirmed that:

- The First-tier Tribunal (“FTT”) have jurisdiction to make RCOs against multiple parties on a joint and several basis, provided that it is just and equitable to do so (which, he was careful to note, will be a “very fact sensitive exercise”);

- The factors which the FTT may take into account when considering whether it is just and equitable to make the order under section 124(1) of the BSA are “very wide” and are not capable of exhaustion;

- Whilst the initial burden is on the applicant to put forward a case as to why it is just and equitable to award an RCO, the evidential burden is ultimately shared between the parties;

- Reference to a building safety risk in section 120(5) of the BSA is a reference to “any risk” which satisfies the conditions of the BSA, and is not a reference to risks above a particular level; and

- The question of whether remedial costs are reasonable will depend on a number of factors, including any reliance on expert reports as to the scope of the works and the time pressure that stakeholders are under to remediate continuing risks to residents.

We highlight our key takeaways for those operating in the construction and property sectors below.

Background to the appeal

The appeal relates to the development of Vista Tower, a residential high-rise building in Stevenage, the freehold of which was sold to the Respondent, Grey GR Limited Partnership (“Grey”) in 2018.

Soon after, post-Grenfell investigations led to the discovery of significant fire safety defects in the building’s external walls and a Remediation Order was issued requiring Grey to remedy those defects by 9 September 2025.

On 24 January 2025, Grey was granted RCOs against 76 corporate entities associated with the developer, Edgewater (Stevenage) Limited (the “Appellants”). Controversially, those RCOs declared each of the 76 Appellants jointly and severally liable for the total sum payable, which was in excess of £13 million.

The RCOs were appealed on a number of grounds.

Joint and several liability for RCOs

The first ground of appeal concerned whether the FTT had the jurisdiction to issue an RCO on a joint and several basis.

The Appellants, in arguing that it did not, relied on the fact that section 124(2) of the BSA describes an RCO as an order against “a specified body corporate or partnership” in the singular, rather than in the plural. In other words, the Appellants said that whilst it is open to the FTT to make a series of orders against different entities, it cannot impose a joint liability under the same order.

Interestingly, in parallel with the RCO application, Grey has commenced proceedings in the High Court (Technology and Construction Court), against the developer and two other Appellants, for a Building Liability Order (“BLO”) pursuant to section 130 of the BSA. Those proceedings have not yet come to trial, but the Appellants’ argument as to the scope of the wording in section 124(2) lead to an interesting analysis of the distinction between RCOs and BLOs.

The UT confirmed that section 130 has a different jurisdiction to section 124, and works in a different way. Section 130 applies where a body corporate has a liability under (a) the Defective Premises Act 1972 or section 38 of the Building Act 1984, or (b) as a result of a building safety risk, and is “fairly rigid in its operation”: the liability to which the original body is subject can be made transmissible to associated parties.

In contrast, under section 124 RCOs are “more flexible and open ended”: it is for the FTT to decide what amount should be paid, and by whom, and on what basis.

Ultimately, Mr Justice Johnson held that the Appellants’ singular interpretation of section 124(2) was too narrow, identifying no reason why it could not be read as a plural. Most significantly, however, he identified an obvious problem with enforcement where one or more respondent is impecunious:

“If one then assumes a situation, which will not be uncommon, where some of the respondents are or may be unable to pay, the applicant party or parties will be left with something resembling a colander, in terms of their ability to recover the total sum ordered to be paid.”

In that scenario, where an applicant is prevented from obtaining the necessary funds for remediation, the statutory purpose of the BSA is clearly frustrated. For that reason, the UT has held that the FTT does have the power to make joint and several RCOs, noting that it will not be the starting position in every case, and that it must carefully consider whether it is just and equitable to do so (which is likely to be a “very fact sensitive exercise”).

Notably, the Appellants also argued that their inability to seek contributions from others in FTT proceedings (pursuant to the Civil Liability (Contribution) Act 1978) was another reason why joint and several liability should not be imposed. However, the UT rejected that argument on the basis that Parliament had intended not to concern itself with the question of contribution in relation to RCOs (but presumably had done so in relation to BLOs, which are pursued via court proceedings) and, in any event, the issue of apportionment/contribution could be dealt with as part of the just and equitable analysis, where circumstances required.

The “just and equitable” test

The Appellants’ secondary position was that it was not just and equitable to grant an RCO as some of the Appellants did not participate in the development, nor profit from it.

The FTT had considered the very limited evidence provided by the Appellants in relation to their corporate structure, and had found that they were part of a “fluid, disorganised and blurred network” which, rather than being financially separate, most likely had a tendency to take from whichever company had money when it was needed by another. The Appellants’ evidence on this point did not impress the UT, with Mr Justice Johnson describing it as “incomplete and unsatisfactory”, a factor which appears to have weighed heavily on him when considering the grounds of appeal.

In rejecting the argument that it was not just or equitable for the FTT to award the RCO on a joint and several basis, Mr Justice Johnson confirmed that the FTT’s discretion is “very wide” and that, in drafting section 124(1), Parliament had chosen not to list or limit the factors to be taken into account. He remarked that, if he were to try and list the factors on which the FTT might rely, he “would be at risk of committing the basic error of attempting to re-write Section 124(1)”.

Mr Justice Johnson also highlighted that, whilst the initial burden is on an applicant to put forward its case as to why it is just and equitable to make an RCO, that burden is not to be overstated, and it is for a respondent to put its case in response.

The meaning of “building safety risk” in section 120(5) of the BSA

One area in which the UT disagreed with the FTT was the meaning of “building safety risk” under section 120(5) of the BSA.

The FTT had defined a “building safety risk” restrictively, as any risk which exceeded the “low” or tolerable category used in PAS9980 assessments. Mr Justice Johnson was careful to correct that interpretation however, advising that section 120(5) “means what it says”.

In other words, it does not refer to any particular level of risk and refers instead to any risk which is captured by the BSA. If Parliament had intended to refer to risk at a particular level, it would have done so (as it had in other parts of the legislation). As no particular level of risk had been referenced in section 120, it was not for the FTT to rewrite the BSA.

Whilst not mentioned in the judgment, that analysis is consistent with the FTT’s recent decision of 6 January 2026 in Canary Riverside Estate (LON/00BG/BSA/2024/0005 LON/00BG/BSB/2024/009) which held that “any risk” of fire spread or structural collapse, however small, is enough to constitute a building safety risk under section 120.

The reasonableness of remedial costs

Finally, the Appellants challenged the reasonableness of one aspect of the costs incurred. Namely, the removal of combustible foam insulation from cavity walls.

Expert witnesses had agreed that, from a purely technical perspective, it had been disproportionate to remove the foam altogether, and a cheaper and simpler solution would have been to leave it in place with the addition of a cavity barrier as effective fire stopping.

In considering the reasonableness of the works, the FTT had placed “significant weight” on the agreement of the experts, but had also considered other factors that may have affected the scope of the works, including the need to implement the remedial scheme quickly in order to minimise the continuing risk to residents living in unsafe conditions, and the fact that Grey’s PAS9980 report had concluded that the foam insulation was “high risk” and needed to be removed.

The Upper Tribunal held that the costs incurred in removing the insulation were reasonable on the basis that it was not for Grey to question the advice of its fire engineers. Rather, it was reasonable for Grey to have relied upon the PAS9980 report and not to have revisited it later in order to reduce the scope of works, especially considering the time pressure it was under from the Secretary of State to minimise the continuing risk to residents.

Implications

The decision reads as a salutary tale to developers and their associates: not only does the FTT have jurisdiction to award RCOs on a joint and several basis, but that jurisdiction may extend to associates who have not participated in the development, or profited from it.

Clearly, that is more likely to be the case where (a) there is a question mark over whether the developer is financially able to meet its responsibility under the RCO, or (b) where respondents fail to provide a comprehensive explanation of corporate structures, or are part of financially fluid networks that cannot easily be isolated, all of which were significant factors in the UT’s reasoning.

Whether the Courts adopt the same analysis in relation to BLOs remains to be seen, although that is a significant possibility given how other UT judgments have been upheld by the Courts (for instance, Adriatic Land 5 Ltd v Long Leaseholders at Hippersley Point [2025] EWCA Civ 856).

Authors

Fenchurch Law – Annual Coverage Review 2025

As the insurance market continues to navigate evolving risks, regulatory frameworks, and geopolitical developments, 2025 has delivered a series of judgments that set important precedents as well as reaffirming established coverage principles. This annual review highlights the key themes emerging from these decisions and their practical implications for those responsible for managing coverage and compliance.

The cases reported this year address critical issues such as the interpretation of policy terms, the scope of notification obligations, the application of fair presentation duties and the classification of policy terms under the Insurance Act 2015. They also explore the impact of third-party rights, insolvency considerations, and principles regarding multiple cover when ‘other insurance’ clauses are in play.

Collectively, these rulings clarify the boundaries of contractual and statutory duties, reinforce the importance of timely and accurate disclosures, and provide guidance on maintaining coverage integrity in complex scenarios.

This round-up aims to equip policyholders and brokers with a clear understanding of the legal trends shaping the insurance landscape, including salutary reminders and pitfalls to avoid.

Unless otherwise stated, the Insurance Act 2015 is referred to as the “2015 Act” and the Third Parties (Rights Against Insurers) Act 2010 as the “2010 Act”.

Insurance Act 2015

- Lonham Group Ltd v Scotbeef Ltd & DS Storage Ltd (in liquidation) (05 March 2025)

In this Judgment, the Court of Appeal issued seminal guidance on how the 2015 Act treats representations, warranties, and conditions precedent. The Court was asked to determine whether the requirements under a Duty of Assured clause were representations or conditions precedent and thus triggering different sections of the 2015 Act.

The policy contained a three‑limb “Duty of Assured Clause” requiring D&S to:

- Declare all current trading conditions at policy inception.

- Continuously trade under those conditions.

- Take all reasonable steps to ensure those conditions were incorporated into all contracts.

The Court was asked to consider whether all three limbs needed to be read collectively (i.e. they would all be classified as either representations or conditions/warranties) or separately (so that each limb was capable of a separate classification). Overturning the decision of the High Court, the Court found that limb 1 was a pre-contractual representation subject to the duty of fair presentation of the 2015 Act, but limbs 2 and 3 were warranties and conditions precedent. As such, in accordance with the 2015 Act, the Insurer had no liability after the date on which the warranty had been breached.

This classification was said to reflect the 2015 Act’s intent: representations allow for proportionate remedies if inaccurate; terms requiring future conduct held to be warranties and/or conditions, by contrast, enable insurers to reject coverage upon breach, provided the terms are clearly drafted.

This decision marked the first major Court of Appeal test of Part 3 of the 2015 Act, and confirms that Duty of Assured clauses can contain both historic representations that go to the Insured’s duty of fair presentation, and warranties as to future conduct, which can have particularly catastrophic consequences if breached. It serves as a reminder to Policyholders and Brokers to scrutinise policy terms and ensure compliance.

Read our full article here.

- Clarendon v Zurich [2025] EWHC 267 (Comm) – Commercial Court Judgment (13 February 2025)

Fenchurch Law acted for Clarendon Dental Spa LLP and Clarendon Dental Spa (Leeds) Ltd, who claimed under a Zurich property damage and business interruption policy after a major fire. Zurich sought to avoid liability, alleging breach of the duty of fair presentation under the 2015 Act for failing to disclose insolvency of related entities.

The Court examined Zurich’s proposal question, “Have you or any partners, directors or family members involved in the business… been declared bankrupt or insolvent…?,” and held that a reasonable policyholder would interpret it as referring only to current directors or partners, not former entities. Consistent with Ristorante Ltd v Zurich (2021), and applying contra proferentem, the Court confirmed that ambiguity in insurer questions is resolved in favour of the insured and that disclosure obligations are shaped by the questions asked at inception.

Overall, the Court concluded Clarendon’s answers were correct and, in any event, Zurich had waived any right to disclosure beyond the scope of its own questions.

Please see our full article here.

- Delos Shipholding v Allianz [2025] EWCA Civ 1019

The Court of Appeal upheld the earlier Commercial Court’s ruling, reinforcing policyholder rights under marine war risks insurance and clarifying the duty of fair presentation under the 2015 Act. The case concerned the bulk carrier WIN WIN, detained by Indonesian authorities for over a year after a minor anchoring infraction. Allianz denied cover, citing an exclusion for detentions under customs or quarantine regulations and alleging non-disclosure of criminal charges against a nominee director.

The Court confirmed the exclusion must be construed narrowly, only detentions genuinely akin to customs or quarantine regulations fall within its scope and the WIN WIN’s detention did not qualify. It also reaffirmed that fortuity remains where the insured’s actions were neither voluntary nor intended to cause the loss. On duty of fair presentation, the Court held the nominee director (who had no decision-making authority) was not part of “senior management” under the 2015 Act, so the Policyholder had no actual or constructive knowledge of criminal charges against him. Further, Allianz had failed to prove that the charges were material and would have induced Allianz to enter into the insurance contract.

Our article on the Court of Appeal Judgment can be found here. Our earlier article on the Judgment of first instance is also here.

- Mode Management Limited v Axa Insurance UK PLC [2025] EWHC 2025 (Comm)

Following a fire on 7 February 2018 at industrial units in Brentwood, Mode (the named insured) and its director (the property owner) sued AXA under a “Property Investor’s Protection Plan” seeking declaratory relief, specific performance (to reinstate/put them back to the pre‑loss position), and other remedies. AXA had avoided the policy ab initio in September 2018 for alleged misrepresentation/non‑disclosure (including questions over insurable interest and planning permission) and applied for summary judgment.

The Commercial Court (Lesley Anderson KC sitting as Deputy High Court Judge) granted AXA’s application. The judge held that the claims were statute‑barred under the Limitation Act 1980, and in any event had no real prospect of success, including the insured’s bid for specific performance of AXA’s alleged secondary liability to reinstate.

The director’s personal claim also failed because he was not a party insured under the policy. The Court emphasised that, on the pleaded facts and policy wording, specific performance was not an available remedy, and the case could be resolved without a trial.

The Judgment can be accessed here.

- Malhotra Leisure Ltd v Aviva [2025] EWHC

During the Covid-19 lockdown in July 2020, a cold-water storage tank burst at one of Malhotra’s hotels, causing significant damage. Aviva, the property damage and business interruption insurer, refused indemnity, alleging the escape of water was deliberately and dishonestly induced by the claimant and that there were associated breaches of the policy’s fraud condition.

The Commercial Court held that Aviva bore the burden of proving, on the balance of probabilities, that the incident was intentional. The Court found that available plumbing and expert evidence supported an accidental explanation, and Aviva’s own expert accepted the escape could have been fortuitous.

The Court also scrutinised Aviva’s allegations of dishonesty in the presentation of the claim, finding that the Fraud Condition must be interpreted in line with the common law, meaning it applies only to dishonest collateral lies that materially support the claim, consistent with The Aegeon and Versloot. Because there was no evidence of dishonesty, and the alleged inaccuracies were either immaterial or inadvertent, the fraud condition did not bite, and Malhotra Leisure was entitled to indemnity.

Please see our full article here.

In a separate costs hearing, the Commercial Court was asked to determine whether costs should be awarded on the standard or indemnity basis. The claimant’s approved costs budget was £546,730.50, but actual costs exceeded £1.2 million, making the distinction significant.

The Court noted that while there is no presumption in favour of indemnity costs where fraud allegations fail, such allegations are of the highest seriousness and, if unsuccessful, will often justify indemnity costs. The Judge found that Aviva’s allegations inflicted financial and reputational harm and were pursued to trial without settlement discussions. As a result, the Court ordered Aviva to pay the claimant’s costs on the indemnity basis, including an interim payment of £660,000, demonstrating the Court’s uncompromising approach towards unfounded fraud allegations.

Please see our full article here.

Effect of Third Parties Rights against Insurers Act 2010

- Makin v QBE [2025] EWHC 895 (KB), Archer v Riverstone [2025] EWHC 1342 (KB), and Ahmed & Ors v White & Co & Allianz [2025] EWHC 2399 (Comm)

This trio of cases highlights the strict approach taken to claims notification provisions in liability insurance policies alongside their impact under the 2010 Act and reaffirms that Claimants under the 2010 Act will have to suffer the consequences of a policyholders breach of conditions.

The Courts confirmed that third-party claimants inherit not only the insured’s rights but also its contractual obligations. Notification clauses were treated as conditions precedent, even where not expressly labelled as such, meaning a breach of these provisions entitled insurers to deny indemnity.

In Makin, Protec Security delayed notifying QBE for three years after an incident that ultimately led to catastrophic injury. The Court held that the obligation to notify arose once Protec reasonably appreciated potential liability which was well before formal proceedings. Ultimately, failure to comply barred recovery.

Similarly, in Archer, R’N’F Catering failed to notify Riverstone promptly and ignored repeated requests for information. The Court rejected arguments that the claimant’s later cooperation could cure the insured’s breach, confirming that rights lost by the insured cannot be revived under the 2010 Act.

Both judgments emphasise that the trigger for notification is not the incident itself but the point at which the insured knows a claim may arise. Excuses such as administrative errors (argument that relevant correspondence had been sent to a spam folder) or insolvency were given short shrift.

By contrast, Ahmed focused on whether notifications made by White & Co to Allianz were sufficiently clear to trigger coverage under a professional indemnity policy. Despite extensive correspondence, the Court found none of the notifications adequately identified the claims or potential liabilities intended to be covered. The judgment underscores that compliance is not just about timing but also clarity and substance, vague or incomplete notices may fail to engage the policy.

The case also illustrates how technical drafting, such as aggregation clauses and endorsements, can compound the consequences of inadequate notification, limiting recovery even where coverage might otherwise apply.

These decisions reinforce several key points for policyholders and claimants:

- Notification clauses, even if unlabelled, may operate as conditions precedent.

- Breaches by the insured cannot be remedied by third-party claimants under the 2010 Act.

- Both timing and clarity of notifications are critical; “can of worms” notifications must be explicit.

- Failure to comply can result in catastrophic loss of indemnity, regardless of claim severity.

Policyholders, with their Brokers' assistance, should adopt a proactive and precise approach to claims notification to avoid disputes and preserve coverage.

Please see our full article on Ahmed here.

The full Judgment on Ahmed is available here.

Aviation

- Russian Aircraft Lessor Policy Claims [2025] EWHC 1430 (Comm).

In a landmark Judgment handed down on 30 June 2025, the Commercial Court determined coverage disputes arising from the grounding and expropriation of hundreds of Western leased aircraft in Russia following the invasion of Ukraine and the imposition of Russian Order 311 in March 2022. The claims, brought by a consortium of lessors including AerCap, DAE, Falcon, KDAC, Merx and Genesis, were the subject of a “mega trial” and resulted in the largest ever insurance award by the UK courts of over £809 million.

The Court held that Contingent Cover responded because the aircraft were not in the lessors’ physical possession and operator policy claims remained unpaid (interpreting, “not indemnified” as “not paid”). Applying a balance of probabilities standard, permanent deprivation was deemed to occur on 10 March 2022, with Russian Order 311 identified as the proximate cause amounting to an effective governmental restraint. This amounted to governmental “restraint” or “detention,” which fell within the Government Peril exclusion under the All-Risks section. Under the Wayne Tank principle, where there are concurrent causes, one covered and one excluded, the exclusion prevails, meaning All Risks could not respond. Consequently, the claims were covered under the War Risks section.

The biggest takeaway for Policyholders from this case, is the guidance that Mr Justice Butcher adopted from the Australian case of LCA Marrickville Pty Limited v Swiss Re International SE [2022] FCAFC 17, which held that:

“The ease with which an insured may establish matters relevant to its claim for indemnity may influence questions of construction … a construction which advances the purpose of the cover is to be preferred to one that hinders it as a factor in construing the policies.”

Please see our full article here.

Building Safety Act 1972

- URS Corporation Ltd (Appellant) v BDW Trading Ltd (Respondent) [2025] UKSC 21

In summary, BDW (being the relevant developer) sued URS (being the design engineers) in negligence for repair costs from structural defects in two development schemes. The Supreme Court was asked to decide whether such voluntarily incurred cost was recoverable and whether section 135 of the Building Safety Act 2022 (“BSA”) extends limitation for such claims.

The Supreme Court unanimously found that once developer knows that defects are attributable to negligent design then remedial works – even on property no longer owned by it – are not ‘voluntary’ in the sense they fall within the ambit of the engineers’ duty. This fortifies the existing common law principles that loss incurred in reliance on professional duty is recoverable, even absent a direct proprietary interest.

The Court clarified that section 135 of the BSA merely extends time for Defective Premises Act 1972 claims and does not revive or extend limitation periods for tortious claims. Policyholders should note that professional indemnity insurers need not cover historic negligence where properly time-barred under the Limitation Act 1980, unless otherwise endorsed.

The Court also held that section 135 of the BSA does not permit developers to treat their negligent repair costs as falling within extended timeframes, preserving clear statutory boundaries between contract/statutory claims and tort claims.

Read our full article on the Supreme Court’s Judgment here.

CAR Policies

- Sky UK Limited & Mace Limited v Riverstone Managing Agency Ltd [2025] EWCA Civ 1567

Insurers sought permission to appeal the Court of Appeal’s December 2024 decision in Sky v Riverstone ([2024] EWCA Civ 1567), which confirmed that deterioration and development damage occurring after the policy period, but stemming from damage during it, was covered under the CAR policy, along with investigation costs and a single deductible per event.

On 30 April 2025, the Supreme Court refused permission to appeal, leaving the Court of Appeal’s ruling intact. This outcome reinforces that insurers cannot restrict recovery to damage physically present at the end of the policy period and affirms a practical approach to progressive damage under CAR policies.

Overall, the refusal cements the Court of Appeal’s interpretation, providing certainty for policyholders on coverage for post-expiry deterioration linked to insured-period damage.

Our article on the Court of Appeal ruling, now confirmed by the Supreme Court’s dismissal is found here.

Latent Defects

- National House Building Council v Peabody Trust [2025] EWCA Civ 932 (CA)

The Court of Appeal resolved a key limitation question over NHBC Buildmark insurance’s “Option 1 – Insolvency cover before practical completion.” Under this extension, insurance is triggered not by the contractor’s insolvency per se but when the employer (Peabody) “has to pay more” to complete the homes because of the insolvency.

The underlying development involved 175 dwellings, including 88 social housing units. The contractor became insolvent in June 2016, and Peabody arranged for completion thereafter, with practical completion in January 2021. The claim for additional completion costs was brought in July 2023. NHBC contended that the cause of action accrued in 2016, when the contractor became insolvent, and was now statute-barred; Peabody argued instead that it accrued when costs were actually incurred.

The Court unanimously agreed with Peabody, affirming the Technology & Construction Court’s view that the policy insured against additional payment triggered by insolvency, so the cause of action only accrued when extra costs became payable. The NHBC appeal was dismissed.

This decision emphasises the importance of carefully identifying the insured event as defined in policy terms and confirms that policies with “pay-when-loss-incurred” triggers should be interpreted on their true wording rather than conventional accrual rules.

The Judgment can be found here.

Other Insurance

- Watford Community Housing Trust v Arthur J Gallagher Insurance Brokers Ltd

This Judgment was a significant ruling clarifying principles concerning multiple cover and a policyholder’s rights following a cyber-related loss. It was a resounding win for policyholders: securing sequential access to multiple policies.

The Court held that Watford had the right to choose which policies to invoke, having the benefit of PI, Cyber and Combined policies, attracting limits of £5 million, £1 million, and £5 million, respectively. Timely notification was made under the Cyber policy, but late notification was successfully raised by the PI insurer to decline indemnity. The Combined insurer confirmed cover despite late notification.

The Court held that the “other insurance” clauses (limiting cover where overlapping insurance exists) effectively neutralised each other, allowing sequential claims rather than enforcing contribution across overlapping policies. This ruling supports the principle that a policyholder can access each policy in turn until the total loss is covered. Having recovered £6 million, Watford also sought recovery of the additional £5 million under the PI policy had timely notification been made. Consequently, Watford was entitled to a total of £11 million.

As to broker liability, the Court found that, but for the broker’s negligence, the PI policy would have been exhausted. Since it was not, the broker was held liable for the £5 million shortfall. The Judgment is a stark reminder that notification conditions should be identified and complied with. It also emphasises a broker’s duty to accurately advise on policy layers and limitations to ensure the policyholder is clearly instructed and that the advice given is documented.

Our full article can be found here.

Authors

Dan Robin Managing Partner

Catrin Wyn Williams, Associate

Pawinder Manak, Trainee Solicitor

Claims Notifications and Policy Terms: A Taxing Duo

Ahmed & ors v White & Company (UK) Ltd & Allianz Global Corporate & Specialty SE [2025] EWHC 2399 (Comm)

BACKGROUND

This case concerned claims (“the Claims”) brought by 176 investors (“the Claimants”) against White & Company (UK) Ltd (“W&C”), a firm of chartered accountants, and its professional indemnity insurer, Allianz Insurance Company (“Allianz”). The Claimants alleged that they had been provided with negligent advice by W&C regarding a series of high-risk tax-mitigation investments. Following W&C’s insolvency, the Claimants sought recovery directly from Allianz under the Third Parties (Rights Against Insurers) Act 2010 (“the TPRAI”).

The central question was whether Allianz was liable to indemnify W&C under its professional indemnity policy for the losses claimed.

THE POLICY

The policy contained the following terms:

The Notification Clause

"The Policyholder shall, as soon as reasonably practicable during the Policy Period, notify the Insurer at the address listed in the Claims Notifications clause below of any circumstance of which any Insured becomes aware during the Policy Period which is reasonably expected to give rise to a Claim. The notice must include at least the following:

(i) a statement that it is intended to serve as a notice of a circumstance of which an Insured has become aware which is reasonably expected to give rise to a Claim;

(ii) the reasons for anticipating that Claim (including full particulars as to the nature and date(s) of the potential Wrongful Act(s));

(iii) the identity of any potential claimant(s);

(iv) the identity of any Insured involved in such circumstance; and

(v) the date on and manner in which an Insured first became aware of such circumstance.

Provided that notice has been given in accordance with the requirements of this clause, any later Claim arising out of such notified circumstance (and any Related Claims) shall be deemed to be made at the date when the circumstance was first notified to the Insurer.”

(“the Notification Clause”)

Related Claims Clause

“any Claims alleging, arising out of, based upon or attributable to the same facts or alleged facts, or circumstances or the same Wrongful Act, or a continuous repeated or related Wrongful Act…shall be deemed to be a single claim”.

(“the Related Claims Clause”)

Tax Mitigation Endorsement

claims arising from investments which were “pre-planned artificial transactions designed to achieve a specific tax outcome” were subject to a single limit of indemnity of £2 million.

(“the Tax Mitigation Endorsement”)

THE ISSUES:

The Court considered three key issues:

- Whether W&C had validly notified Allianz of the claims or circumstances that might give rise to claims pursuant to the Notification Clause.

- Whether the claims should be aggregated under the policy’s “Related Claims” clause; and

- Whether the Tax Mitigation Endorsement applied.

JUDGMENT

Notification

As part of determining whether the Claims had been validly notified, the Court was asked to consider whether the following three categories of communications constituted a valid notification of all Claims pursuant to the Notification Clause.

- The “Akbar Letters”

These were letters written by the Claimants’ solicitors to W&C, outlining details of specific investments and the alleged negligent advice provided by W&C in relation to those investments.

The Claimants argued that forwarding these letters to Allianz constituted a broad notification, sometimes referred to as a “hornets’ nest” notification, which should be interpreted as alerting Allianz to the possibility of further claims from other clients who had received similar advice, not just the 14 named entities. Allianz, on the other hand, argued that the notification was limited strictly to the 14 specific entities mentioned in the letters and did not extend to any other potential claimants.

Considering all the evidence presented, the Court found in favour of Allianz that the language did not signal a “hornet’s nest” scenario, indicating an influx of future claims. In coming to this decision, the Court stressed that any notification must be clear and specific. In contrast, the Akbar Letters did not provide sufficient information to put Allianz on notice of a broader class of claims.

- The “Block Notification”

These communications between W&C and Allianz contained information regarding HMRC inquiries into premature EIS relief, along with a spreadsheet. An EIS (Enterprise Investment Scheme) is a UK government initiative that encourages investment in small, high-risk companies by offering tax reliefs to investors. The relevance in this case was that the investments in question were structured to take advantage of EIS tax reliefs, and HMRC inquiries suggested that the reliefs may have been claimed prematurely or improperly.

The Claimants argued that the Block Notification, which included details of the HMRC inquiries and a spreadsheet of affected clients, should have been interpreted as a notification of circumstances that might give rise to multiple claims against W&C. Allianz, however, interpreted this notification as relating solely to another entity MKP, which W&C had acquired and not W&C itself, and argued that it did not provide sufficient detail or context to constitute a valid notification of claims or circumstances under the policy.

In the Court’s judgement, a reasonable insurer in Allianz’s position would have perceived the Block Notification as limited, and not indicative of wider claims against W&C, as it did not clearly identify W&C as the subject of the potential claims, nor provide enough information to alert Allianz to the risk of multiple claims. The Court noted that while W&C may have had the subjective awareness of the broader matters, that awareness was not communicated to Allianz and therefore was not within the scope of the notification.

- The “Kennedy Documents”

These were emails between defence counsel, their clients, W&C, Allianz, and the claimants’ lawyer. The documents included correspondence and information that might have disclosed sufficient facts to support a broader notification of circumstances. The Claimants argued that these communications, by virtue of being shared with Allianz, should be treated as a valid notification under the policy. However, Allianz contended that the policy required notifications to be made “by the insured,” and that communications from solicitors or third parties did not satisfy this requirement, unless there was express contractual authority for them to notify on W&C’s behalf.

In his judgment, Judge Pearce noted that such documents might have disclosed sufficient facts to support a broader notification. However, as W&C itself did not communicate them and, absent express contractual authority for W&C’s solicitors to notify on its behalf, Allianz’s receipt did not satisfy the policy’s requirement that any notifications come “by the insured”.

Overall, the Court determined that no communication effectively notified Allianz of broader circumstances or triggered wider policy cover. Only narrow notifications of specific claims, by reference to specific investments, were valid. Hence, policyholders should note the importance of strict compliance with policy notification requirements and the need for clarity and specificity in any notification to insurers.

Aggregation and Endorsement

Judge Pearce then addressed the alternative arguments on aggregation and policy limits if the matters had been validly notified.

Tax Mitigation Endorsement:

This endorsement applied to tax-mitigation schemes such as pre-planned, artificial transactions aimed at achieving specific tax outcomes (including EIS). The Claimants contended that the endorsement should not apply to all the investments in question, or that its application should be limited. Allianz argued that the endorsement was triggered by the nature of the investments, which were designed to achieve specific tax outcomes through artificial means, and that the £2 million limit therefore applied to all claims.

The Court agreed with Allianz, finding that the endorsement applied and that the Claimants’ demand for £50 million was subject to the £2 million limit.

Related Claims Clause

The policy defined related claims as those arising from the same facts, circumstances, wrongful act, or a related wrongful act. The Claimants argued that each investor’s claim should be treated separately, potentially allowing for multiple limits of indemnity to apply. Allianz, conversely, argued that all claims arose from the same or related acts, namely, W&C’s advice on tax mitigation schemes, and should therefore be aggregated as a single claim under the policy.

Supporting Allianz, the Judge found that each of the investor claims relating to EIS stemmed from the same alleged misconduct by W&C, namely, negligent advice on tax‑mitigation schemes and therefore were sufficiently “related” to aggregate as one claim. However, the non-EIS claims were not sufficiently related.

KEY TAKEAWAYS

Overall, this decision is a reminder of the strict approach towards claim notifications and the application of policy terms. Policyholders must ensure notifications are clear, complete and timely, as ambiguous or narrow notifications risk leaving policyholders without cover. Equally, it is critical for policyholders to understand the wording of their insurance policy and be alive to terms that limit cover via aggregation clauses, to ensure policy coverage aligns with risk exposure.

Chloe Franklin is an Associate and Pawinder Manak is a Trainee Solicitor at Fenchurch Law.

When can an insurer join the party? Managed Legal Solutions v Mr Darren Hanison (trading as Fortitude Law) and HDI Global Specialty SE [2025]